Why stablecoins will NOT destroy the euro (in fact, they could help it)

Briefly, this article can be applied to multiple jurisdictions, even though the focus today is on euro area stablecoins. The argument, however, generalises easily: the risks attributed to stablecoins are far less dramatic than many commentary pieces suggest. More specifically, this text is written as a response to the growing number of articles that paint an apocalyptic scenario in which stablecoins could “destroy” the euro (as claimed, for instance, here; a similar fear has also emerged in the UK, as discussed here).

Yet the claim that stablecoins could destroy the euro depends on a misunderstanding of what stablecoins actually are, how monetary sovereignty functions within the euro area, and the dynamics of cross-border currency use. In more detail, this alarming claim of “stablecoins could destroy the euro” rests on a simple intuition: if private digital tokens denominated in dollars or euros become ubiquitous as means of payment and store of value, households and firms might choose those tokens over bank deposits or domestic currency, in this process undermining monetary sovereignty and to some extent the central bank’s control over the money supply. That fear is magnified if the dominant stablecoins are dollar-pegged, as the real worry becomes a version of digital dollarisation, where the euro area’s domestic payments and saving settle increasingly in USD-linked tokens. This is also something I examined in detail in a previous post, where I unpacked the geopolitics of stablecoins, instruments that are already being used, or could easily be used, by certain states to expand or reinforce the global reach of their currencies. I argued there that Europe must embrace euro-denominated stablecoins if it wants to counter, successfully or not, the Trump administration’s explicit effort to further internationalise the dollar through stablecoin infrastructure.

Returning to the main point, it should be stated clearly from the outset that, before anything else, stablecoins are not independent monetary systems capable of undermining the euro’s foundations. They are balance-sheet instruments whose stability depends entirely on the credibility, liquidity, and/or regulatory oversight of the very sovereign currencies they purport to “replace”. In the case of euro-denominated stablecoins, their functioning is inseparable from the liquidity of euro money markets and the supervisory authority of the Eurosystem. That’s why I consider stablecoins to be an infrastructure layer built on top of the euro, not necessarily an alternative to it.

The concern expressed in a recent commentary is that if stablecoins achieve wide adoption they could disintermediate banks and shift payments outside the reach of regulators. Not to mention they could weaken the role of central bank money as the anchor of the financial system. There are several problems with this argument. Stablecoins do not eliminate the euro’s monetary architecture, they merely reproduce it in an inferior and more constrained form. A euro stablecoin does not create private money out of nothing. It creates a token whose value depends entirely on the issuer’s ability to hold (and redeem) euro assets. Even those who argue that stablecoins pose systemic risk implicitly rely on this premise. A stablecoin that does not maintain full backing loses its peg, collapses in value, and stops functioning as a payment instrument, as demonstrated by stress events such as TerraUSD in 2022 (see this working paper from Bank for International Settlements for a detailed analysis). But a fully backed euro stablecoin is nothing more than an alternative wrapper around euro deposits or short-term sovereign securities, among others.

In other words, stablecoins have no monetary sovereignty. They mint no base money, control no lender of last resort, and set no interest rate. They depend entirely on the euro’s monetary ecosystem for survival. European regulation confirms this. Under the EU’s Markets in Crypto-Assets Regulation (MiCAR) framework, stablecoins are legally classified as “asset-referenced tokens” or “e-money tokens” and are subject to strict reserve and redemption rules. Those regulatory rules mean euro stablecoins are not outside the sovereign sphere. Moreover, the text of MiCAR itself (Regulation EU 2023/1114) requires that issuers “constitute and at all times maintain a reserve of assets … in such a way that … the liquidity risks associated to the permanent rights of redemption of the holders are addressed", as can be read here.

Arguments that a private issuer could leverage a euro stablecoin to accumulate excessive influence in payments or credit rest on the flawed assumption that payment architecture confers monetary control. But payment rails do not determine monetary control. Visa and Mastercard already move trillions of euros globally without undermining the euro1. Money-market funds hold vast amounts of euro assets without destabilizing monetary sovereignty. Even the Eurodollar market, the largest offshore currency system in the world, did not destroy the dollar (nor the Euro). Euro-denominated stablecoins are structurally much closer to e-money funds than an offshore “shadow currency”. They do not create endogenous credit, they do not expand through fractional reserves, and under MiCAR issuers must hold 1:1 reserves in high-quality liquid assets with redemption rights enforceable in euros.

If anything, sovereign jurisdictions lose more monetary control when a foreign currency replaces the domestic unit of account, rather than when tokenized versions of the domestic currency circulate. For instance, dollar stablecoins circulating in emerging markets can undermine local currencies (a concern often raised by the Bank for International Settlements, see for example here). However, a euro-denominated stablecoin circulating within Europe does not undermine the euro, as it does not compete with the monetary base. It is the euro going digital via private rails, that’s all. Also, a deposit at a commercial bank is not just a private I Owe You (IOU), it is a claim within a legal framework and (crucially) redeemable into central-bank money. Central banks underpin settlement systems and provide finality, something private tokens do not replicate by design. Even if a euro stablecoin becomes widely accepted for retail payments, it does not automatically confer the same legal and systemic status as central-bank money. The ECB and national central banks remain the monopoly issuer of central bank currency and settlement finality in the euro area.

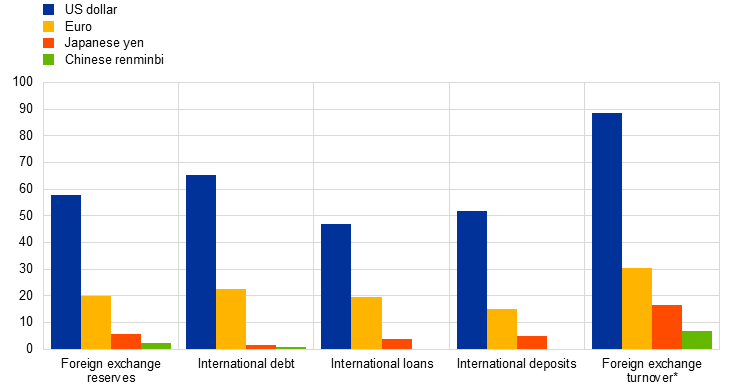

This distinction matters deeply because the euro’s greatest weakness has never been private tokenization. It has been its limited international use compared to the US dollar. The ECB’s report on the international role of the euro shows that, while the euro remains important, its share in global payments and reserves has not materially increased in recent years, especially when compared to the USD.

Source: European Central Bank

Meanwhile, dollar-denominated stablecoins like USDT and USDC have grown enormously, not because they threatened the dollar’s sovereignty, but because they offer convenient distribution in markets that already use the dollar (both stablecoins were also discussed in my post about geopolitics of stablecoins). They are distribution technologies, if you want, not monetary technologies. The same reasoning applies to euro stablecoins, as they offer a mechanism to spread the euro’s use, not to undermine it.

The euro’s adoption outside the euro area has always been held back by structural issues, such as fragmented capital markets, unharmonized fiscal policy, and a lack of a truly unified euro-area safe asset. Stablecoins cannot fix these macro-institutional problems, but they can offer a more efficient means for euro liquidity to circulate globally. In decentralized finance, offshore financial centers, or emerging markets with strong demand for euro stability, euro stablecoins can provide frictionless access to euro settlement. In this context, they are a vector for euro internationalization.

Some worry that private stablecoins might replace bank deposits. That too misunderstands banking intermediation. If stablecoins scale, the institutions backing them will hold more euro assets, deposits, commercial bank money, sovereign bills, repo positions, you name it. These flows re-enter the regulated banking system. A euro held in a stablecoin reserve account is still a euro deposit in a bank, unless the issuer holds it at a central bank, a structure MiCAR discourages for issuers aiming at scale to avoid concentration of central bank liabilities in private stablecoin vehicles. More than that, for a stablecoin to really substitute at scale for bank deposits or cash you need a global, liquid market for that token, easy conversion into goods and services, and reliable fiat on- and off-ramps. Building that market is costly and requires trusted institutions at both ends. Major banks, card networks and payment processors control most of those rails today. Private stablecoins must either partner with incumbents or recreate that stack, both hard and expensive. Past examples (crypto or otherwise) show that critical mass is very difficult to reach absent a strong value proposition (e.g., much lower cost, greater convenience). So this is a worry we shouldn’t have. In plain English, if a stablecoin issuer fails, users can redeem back into euros. And before anything, redemption risk is a microprudential issue, not a macro-monetary threat.

The only realistic scenario in which stablecoins could threaten monetary sovereignty is if they become large enough to absorb a major portion of high-quality euro collateral (e.g., short-term sovereign bills) and thereby influence short-term interest rates. But this is not a euro-only risk; it applies to any large money-like nonbank vehicle, including money-market funds. Crucially, the euro area does not have a single unified short-term sovereign market the way the US does. Stablecoin issuers would face fragmentation risk and diverse sovereign spreads (uneven collateral availability). Any attempt to aggressively scale euro stablecoins would confront the eurozone’s own structural fragmentation, from fragmented government debt markets to cross-country differences in credit risk(s).

In short, stablecoins are fundamentally infrastructure. They do not replace the euro. They can expand where traditional banking is weak, open new rails, or improve access for cross-border participants. But they cannot, by themselves, destroy the euro’s monetary sovereignty or institutional legitimacy. If well regulated, they may in fact accelerate the euro’s international footprint rather than erode it. As such, stablecoins will not destroy the euro, but Europe risks geopolitical subordination if it fails to build euro-denominated stablecoin infrastructure (because USD-denominated stablecoins are here to stay!)

If anything, the policy debate should flip. Treat well-regulated euro-stablecoins and a digital euro as two complementary channels to broaden euro use while protecting monetary sovereignty. Done right, stablecoins could be a vehicle for euro internationalisation; done wrong (or left unregulated), they could create pockets of substitution with real costs. The difference will be made by laws and oversight, not by distributed-ledger novelty alone.

Alexandru Stefan Goghie is a PhD candidate in the Department of Political and Social Sciences at Freie Universität Berlin, PhD researcher at JFKI’s Graduate School of North American Studies and PhD researcher at Global Climate Forum. His research focuses on geopolitics, the global financial system, monetary policy, and the geopolitics of finance”. You can follow him on his Substack https://goghieas.substack.com/