Are stablecoins really leading to the “privatization of money”?

A few days ago, Christine Lagarde made waves at a conference in Lisbon when she expressed, let’s say, a certain skepticism about the benefits of stablecoins, arguing that they would in effect lead once again to the “privatization of money”. At first glance - or if we look at the issue of stablecoins “from the moon” - it might indeed seem that way. But her statement starts to look a bit superficial once we actually understand how stablecoins function (or could function).

Before anything else, though, it’s important to clarify what exactly she meant by this “privatization of money.” Throughout history, the idea of privatizing money has surfaced in different forms, most notably during the so-called “Free Banking” era of the 19th century. In places like Scotland (1716–1845) and the United States (1837–1863), banks issued their own banknotes, each circulating as a medium of exchange and backed by the issuer’s reserves, often a mix of specie (gold or silver) and financial assets. The system was based on competition: banks were supposed to discipline each other, since over-issuance of notes could lead to inflation, runs and ruin the issuer’s reputation. You can read more on this subject here.

In practice, this era highlighted both the promise and the peril of privatized money. On the one hand, it demonstrated how private banks could create and distribute money efficiently, stimulating commerce and investment. On the other hand, it exposed the vulnerabilities of a decentralized monetary system: frequent bank failures, chaotic note redemption, and widespread instability. The very fact that each bank’s note traded at a discount depending on distance, perceived solvency, and the quality of its backing made clear the absence of a truly uniform and trustworthy national currency. Moreover, it was a cumbersome system. For instance, back then, it was common to see “banknote reporters”, meaning publications listing daily discount rates on notes from thousands of banks. Worse, “wildcat banks” would pop up solely to issue excessive notes, then vanish, leaving holders with worthless paper. Bank failures and runs were frequent, shaking public trust.

It is precisely these weaknesses that led to central banking reforms that influence our daily lives today, think about central banks that were empowered to provide lender-of-last-resort functions, national banknotes that were standardized, and private money issuances that were largely curtailed. Of course, this last observation brings me to another important point: are money and near-money truly not privatized today? After all, there’s already a broad consensus (unless you belong to the Austrian School of Economics) that money is endogenous rather than exogenous, in other words, it is created by banks through the process of lending. Put differently, it is loans that create deposits, not the other way around (contrary to what the Austrian School would argue).

The Eurodollar system is perhaps the best illustration of this dynamic (more briefly explained here). Without drifting too far off topic, it’s clear that money creation today remains largely privatized: while central banks do play a role by issuing base money, the creation of broad money is fundamentally a private function. The difference is that this process now operates within a regulated domestic framework and uses a unit of account (the USD, EUR, JPY, you name it) imposed by the state. And if we take the discussion even further, we see that a significant share of today’s economic activity is also tied to shadow money.

For those unfamiliar with the term, shadow money is a concept that emerged from the study of the financial crisis of 2007-2009, when certain financial structures faced a sudden loss of confidence, resembling a “run” like in traditional banking, but outside the official banking system. Unlike traditional banks, which create money autonomously by issuing loans and deposits on their balance sheets, shadow banking involves credit creation through a network of non-bank financial intermediaries. These intermediaries perform banking-like functions - such as credit intermediation and liquidity provision - but do so across multiple connected entities rather than a single institution.

In a nutshell, shadow money refers to the money-like private debt instruments created within this shadow banking system. While the Financial Stability Board originally treated shadow banking as a “non-monetary phenomenon”, it is quite clear that shadow banking also creates forms of money, private debt instruments that can act as near-money or alternative money substitutes.

To classify an instrument as shadow money (you can read more about shadow money here but also here), three main criteria are often used:

- It is demanded as an alternative to traditional money (like bank deposits).

- It trades at or near par value with bank deposits, meaning it’s widely accepted as a high-ranking form of money.

- It is created through the swapping of private debt claims (IOUs), much like how banks create money by issuing loans.

Examples include repurchase agreements (repos), asset-backed commercial paper (ABCP), money market fund (MMF) shares, and certain foreign exchange swaps. Whether these qualify as shadow money depends on how strictly these criteria are applied, as the boundary between money and credit remains fluid and historically contingent.

In short, shadow money broadens our understanding of modern money as a spectrum of credit instruments beyond traditional bank deposits, highlighting how private financial markets generate money-like assets that can influence liquidity and financial stability. Thus, money and near-money today are predominantly created by the private sector. So what risk of “money privatization” are we still talking about? Well, Christine Lagarde would probably tell me to go back to the issue of “Free Banking”, because that’s where this so-called “privatization” threatens to undermine monetary policy.

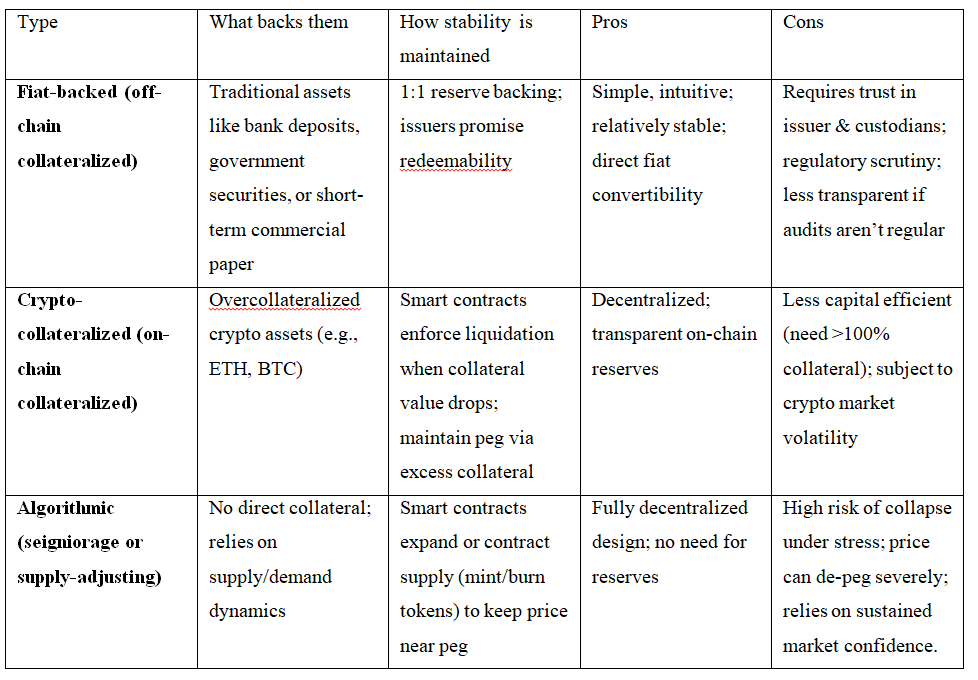

So the debate about “Free Banking” has resurfaced in the context of stablecoins. For more clarity, stablecoins are a category of digital tokens designed to maintain a stable value relative to a reference asset or measure of worth. Today we have three large stablecoins models:

- Asset-backed models, where tokens are fully or partially collateralized by fiat deposits, even CPI-indexed currencies (this stablecoin is co-developed by Andrew Fately, a frequent commentator on this blog, so if needed, he can provide us with even more insights), government securities, or other low-risk assets.

- Crypto-collateralized models, where tokens are backed by excess collateral in cryptocurrencies to absorb volatility.

- Algorithmic models, where smart contracts adjust the supply of tokens automatically to keep the price close to the target.

More details in the table below:

Source: Author’s illustration

For today, we will focus on the asset (or fiat)-backed models, meaning stablecoins as digital tokens pegged to fiat currencies like the US dollar, euro, or yen. In this context, it is true that at first glance, stablecoins might appear to repeat the mistakes of the “Free Banking” era: privatizing money by letting private issuers create widely used digital dollars that circulate outside the banking system and central bank oversight. As they say, if left unchecked, this could again fragment the monetary system, weaken monetary policy, and increase systemic risk.

Yet this analogy isn’t perfect. Rather than replacing the USD or the EUR, stablecoins function as digital wrappers, new technical forms of old money. In theory, they could preserve the stability and credibility of public money if properly regulated. The risk of privatization arises not just from the issuance itself, but from the structure and regulation of the issuers.

For example, if private issuers like Tether or Circle hold reserves in opaque offshore entities, backed partly by riskier commercial paper or long-dated securities, then the peg depends on the market’s trust in those reserves. If large enough, such a system could become systemic: a sudden loss of confidence might trigger mass redemptions, force asset fire sales, and threaten financial stability. In that sense, stablecoins could indeed replicate some of the instability of the “Free Banking” era. But we encounter the same issue even beyond stablecoins. Let’s not forget the problems during the Global Financial Crisis, when it wasn’t only shadow banks that were affected, but also traditional banks.

Thus, the possibility of a sudden loss of confidence isn’t inevitable (and it shouldn’t be). The same technology could be embedded within the regulated financial system. For instance, imagine if Tether were to obtain a special banking license allowing it to issue stablecoins fully backed by safe central bank reserves or fiat-backed digital tokens. And I want to emphasize the word special: there could be a dedicated regulatory category, a separate framework that allows these institutions to fast-track the process of obtaining a banking license, provided they can demonstrate the capacity to meet macroprudential criteria and commit exclusively to the specific activity of issuing stablecoins.

And voilà! This wouldn’t create a parallel monetary system; it would simply offer a new digital interface layered over the existing sovereign currency. The coins would still circulate privately (as they already do), but their ultimate backing and settlement would remain public. From the user’s perspective, it would feel modern and flexible, yet the foundations of the system would continue to be anchored within the central bank’s control.

Therefore, there are several ways stablecoins could avoid leading, in practice, to a “privatization of money”. One example, as already mentioned, is by re-anchoring stablecoins to central bank money. If stablecoins become systemic before regulation catches up, the first corrective move is to require issuers to fully back their tokens with deposits at the central bank. Rather than holding short-term T-bills, commercial paper, or other market assets, the issuer would maintain a 100% reserve balance at the Fed, ECB, or another central bank. This preserves the stablecoin as a private medium of exchange - users still transact with Tether or Circle tokens - but the ultimate backing is sovereign. The issuer can’t create new tokens beyond the reserves it holds, so money creation is limited. Liquidity risks largely vanish, since redemptions are matched by reserves at the highest-quality, risk-free institution. Instead, this brings us to the discussion around synthetic central bank digital currencies (synthetic CBDCs). In more details, a synthetic CBDC isn’t truly a central bank digital currency itself. Instead, it refers to a stablecoin issued by a private entity (of Tether, Circle or or any other regulated bank), whose value is fully backed by funds kept directly in a central bank master account. In practice, this means the stablecoin’s issuer holds customer funds as reserves at the central bank, ensuring the tokens remain fully redeemable and benefit from the same safety and liquidity as other deposits placed at the central bank. The stablecoin functions much like existing fiat-backed tokens but gains an added layer of security and trust by having its reserves directly parked with the central bank, rather than in commercial banks or other financial institutions.

Moreover, building on the point above, there is also the possibility to restore the direct transmission of monetary policy. For instance, central banks could directly shape demand for stablecoins through interest rates. If stablecoins are backed by reserves, the central bank’s policy rate - via interest on those reserves (it is something that’s also happening today, as I discussed here) - immediately affects the cost structure of the issuer. Alternatively, stablecoins themselves could be made interest-bearing, passing on rate changes to end-users. In either case, the central bank regains an essential lever: by tightening or loosening policy, it directly influences the incentives to hold and use these digital assets, just as it does with traditional bank deposits.

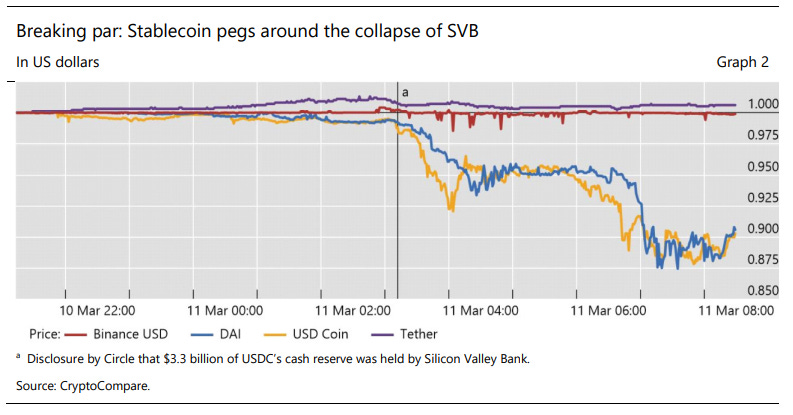

As a curious anecdote, let’s not forget that after the Silicon Valley Bank episode, the Federal Reserve effectively ended up providing a backstop - acting as a lender of last resort - for USDC, a stablecoin. This happened because USDC had held substantial deposits at SVB as part of its supposedly liquid reserves. In the figure below, we can also see how SVB, given its close ties to the crypto market, had an impact on the liquidity of some of the largest stablecoins. This illustrates why there’s a debate about the so-called risks of “money privatization.”

Source: Bank of International Settlements

But there is still another solution, which I consider relatively more appropriate: to “force” stablecoins into the regulated banking perimeter. Beyond just requiring full backing, authorities could demand that issuers become licensed banks. This means complying with capital and liquidity requirements, risk management standards, and regular audits. It also subjects them to supervision by central banks and other prudential regulators. Inside the banking perimeter, stablecoin issuers could earn money by offering loans, investing reserves, or providing payments services, rather than relying solely on management fees. This approach doesn’t privatize money; instead, it digitizes bank deposits in token form (so we have stablecoins underlying fiat currencies), sometimes called “tokenized deposits”. The coins remain part of the traditional banking system, and monetary policy continues to influence them directly, because issuers face the same reserve requirements and funding costs as other banks. This idea seems to be gaining increasing traction. Less than ten days ago, Circle Internet Group applied for a national trust bank charter license, with the explicit goal of integrating stablecoins into the traditional financial system. The institution intends to call itself First National Digital Currency Bank, N.A., becoming only the second entity of this kind to obtain a banking license, after Anchorage Digital.

In summary, this post aimed to show that the mere rise in the importance of stablecoins does not necessarily mean a “privatization of money” along the lines of the “Free Banking” model. It is enough for certain policymakers to set aside their pride and accept that we are part of a fundamental transformation of the financial sector and that the best thing they can do is to lend a helping hand, not to stir fear. I know there will be people who disagree with me, who reject the idea of seeing regulation as the best friend of innovation. But as you will see, I am as pragmatic as it gets. In other words, I don’t dwell on ideal scenarios; I try to focus on practical ones. And at this moment, with the risk of being wrong, a legal combination of stablecoins and regulated banks represents the fastest way to achieve true mass adoption of these instruments. Time will tell which solution is ultimately best!

Alexandru Stefan Goghie is a PhD candidate in the Department of Political and Social Sciences at Freie Universität Berlin, PhD researcher at JFKI’s Graduate School of North American Studies and PhD researcher at Global Climate Forum. His research focuses on geopolitics, the global financial system, monetary policy, and the geopolitics of finance”. You can follow him on his Substack https://goghieas.substack.com/